Archive for October, 2015

Physics and philosophy

Rogério Rosenfeld took part in debates with Antonio Cicero on the 5th Art and Science edition, and discussed what we currently know and don’t know about the universe

Over the last few weeks, Rogério Rosenfeld, current director of IFT/Unesp and vice-director of ICTP-SAIFR, took part in a series of debates to talk about science and his area – from the microscopic world of Particle Physics to the macroscopic one of galaxies and the universe. The events were part of the 5th Art and Science edition, which brings together professionals from different areas for a series of lectures and discussions in cities throughout Brazil.

Click here to watch one of Rogério Rosenfeld’s talks on the 5th Art and Science edition.

“I enjoyed being part of this initiative because I had the opportunity to talk about science and about my area for the general public, and I think science communication is essential”, says Rogério.

Of the four debates Rogério participated in, three were with the philosopher Antonio Cicero. The theme of these events was the universe: how is the dialogue today between physics and philosophy when it comes to its origin and its mysteries, as dark matter and dark energy?

What we know that we know

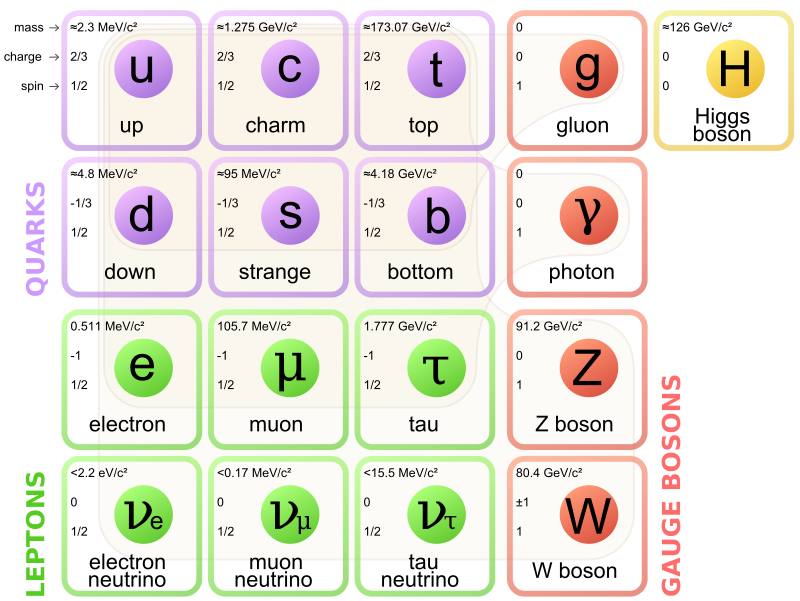

In his lectures, Rogério first talked about “what we know that we know” about the universe. At the microscopic extreme, we learned over the centuries that matter is consisted of atoms, that they are divisible into electrons and the nucleus, and that the nucleus is made of neutrons and protons. With scientific and technological advances, we discovered that even these particles could be broken down into quarks. And so the Standard Model was created – a kind of periodic table of the elementary particles of nature. The last major discovery in the area was the detection of the Higgs boson at the LHC in 2012, which completed the model.

In the macroscopic end, we know the age of the universe – 13.7 billion years – we know that it is not static – it’s expanding – and in 1998 we found out that, contrary to what everyone thought, the expansion is accelerating. We also know that the universe is composed of only about 5% of matter as we know it – 24% is dark matter and 71% is dark energy.

What we know that we don’t know

Then Rogerio talked about “what we know that we don’t know”.

“There’s a lot we don’t know about the universe, but at least we know that we don’t know, which is very important,” said Rogério.

An example is the existence of particles beyond the Standard Model – there is the possibility that there are particles in the universe which we couldn’t observe until today. We also know that we don’t know what is dark matter made of and what is dark energy, responsible for the mysterious accelerating expansion of the universe.

“I just didn’t talk about what we don’t know that we don’t know because… I don’t know it”, said the researcher.

Debate

In his talk, Antonio Cicero spoke mainly about the Ápeiron. The word of Greek origin, that means “unlimited, infinite,” refers to the central idea of a cosmological theory created by Anaximander in the sixth century BC. According to it, the ultimate reality, called arché, is eternal and infinite and is not subjected to age or disintegration.

Rogerio provoked Antonio Cicero saying that, in physics, the infinite doesn’t exist.

“How many grains of sand are there on a beach? How many atoms on the planet? A lot, but not infinite. When, in a theory, we find an “infinite”, we know that there is a problem with it”.

The debate was followed by questions from the audience and, at the end, Rogério and Cícero agreed that, despite the fact that philosophy and physics had the same origin, today the areas are quite different.

Click here for more information on the Art and Science events.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Physics and philosophy

Física e filosofia

Rogério Rosenfeld participa de debates com Antônio Cícero no 5º Ciclo Arte e Ciência, e discute sobre o que atualmente sabemos e não sabemos a respeito do universo

Ao longo das últimas semanas, Rogério Rosenfeld, atual diretor do IFT/Unesp e vice-diretor do ICTP-SAIFR, participou de uma série de debates para falar sobre ciência e sobre sua área – desde o universo microscópico da Física de Partículas até o macroscópico das galáxias e do universo. Os eventos fizeram parte do 5º Ciclo Arte e Ciência, que reúne profissionais de diferentes áreas para uma série de palestras e debates em cidades espalhadas pelo Brasil.

Clique aqui para ver uma das palestras de Rogério Rosenfeld no 5º Ciclo Arte e Ciência.

“Gostei de participar da iniciativa, pois tive a oportunidade de falar sobre ciência e sobre a minha área para o público geral e acho que fazer divulgação científica é essencial”, diz Rogério.

Dos quatro debates que Rogério participou, três foram com o filósofo Antônio Cícero. O tema dos eventos foi o universo: como está hoje o diálogo entre física e filosofia quando se trata da sua origem e de seus mistérios, como matéria e energia escura?

O que sabemos que sabemos

Em suas palestras, Rogério falou primeiro sobre “o que sabemos que sabemos” em relação ao universo. No extremo microscópico, aprendemos ao longo dos séculos que a matéria é constituída por átomos, que eles são divisíveis em elétrons e núcleo, e que o núcleo é composto por nêutrons e prótons. Com o avanço da ciência, descobrimos que até essas partículas podem ser quebradas em quarks. Assim, foi criado o Modelo Padrão – uma espécie de tabela periódica das partículas elementares da natureza. A última grande descoberta da área foi a detecção do Bóson de Higgs pelo LHC em 2012, que completou o Modelo.

Já no extremo macroscópico, sabemos a idade do universo – 13,7 bilhões de anos -, sabemos que ele não é estático – está expandindo – e, em 1998, descobrimos que, ao contrário do que todos pensavam, a expansão é acelerada. Sabemos também que o universo é composto por apenas cerca de 5% de matéria como a conhecemos – 24% é matéria escura e 71% é energia escura.

O que sabemos que não sabemos

Em seguida, Rogério falou sobre “o que sabemos que não sabemos”.

“Há muito que não sabemos sobre o universo, mas pelo menos sabemos que não sabemos, e isso já é muito importante”, disse Rogério.

Um exemplo disso é a existência de partículas além do Modelo Padrão – há a possibilidade de que existam partículas no universo que nós não conseguimos observar até hoje. Também sabemos que não sabemos do que é feita a matéria escura e o que é a energia escura, responsável pela misteriosa aceleração da expansão do universo.

“Só não falei sobre o que não sabemos que não sabemos porque…eu não sei”, brincou o pesquisador.

Debate

Em sua palestra, Antônio Cícero falou, principalmente, sobre o Ápeiron. A palavra de origem grega, que significa “ilimitado, infinito”, se refere à ideia central de uma teoria cosmológica criada por Anaximandro, no século VI a.C. De acordo com ela, a realidade última, chamada de arché, é eterna e infinita e não está sujeita a idade ou desintegração.

Rogério provocou Antônio Cícero afirmando que, na Física, o infinito não existe.

“Quantos grãos de areia existem em uma praia? Quantos átomos no planeta? São muitos, mas não infinitos. Quando, em uma teoria, encontramos um “infinito”, sabemos que há um problema com ela”.

O debate seguiu com perguntas do público e, ao final, Rogério e Cícero concordaram que, apesar da origem da Filosofia e da Física ser a mesma, hoje as áreas são bastante diferentes.

Para saber mais sobre o Ciclo Arte e Ciência e seus eventos, clique aqui.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Física e filosofia

Complex networks and neuroscience

Throughout the School on Complex Networks and Neuroscience, held at ICTP-SAIFR from September 28th to October 16th, Claudio Mirasso, from the Universitat de les Illes Balears, in Spain, talked about the relation between complex networks and brain research. The physicist, who was also one of the event’s organizers, pointed out how, on one hand, ideas from physics can help us understand neuroscience and, on the other, the way the brain functions may contribute to research in physics.

Brain Functioning

One of Mirasso’s interests is understanding the synchronization between different brain regions.

“In electroencephalography (EEG) studies we see that different brain regions, often not structurally connected, are synchronized”, he says. “Through studies with complex networks, we try to understand this synchronization and the exchange of information between different brain areas”.

One of the reasons for the synchronizations, according to the researcher, is that regions have similar or complementary roles. When we see an object, for instance, information about its shape, color and position in space are sent to the brain, and different areas are activated to process this set of data.

“Among our most recent results, we found that the thalamus is one of the main areas responsible for coordinating this synchrony”, said Mirasso.

Information Processing

If complex networks help us understand how the brain works, the opposite can also happen – especially when it comes to processing information.

“We are living in the era of information”, says Mirasso. “The amount of data we have increases every day, so we need new ways to process all this information”.

One way to make this processing more efficient is to previously sort only the data of interest. This is the technique used by the brain: every second we are bombarded with thousands of visual, sensory and auditory stimuli. However, just relevant information is processed.

“Studying how the brain filters and processes information and trying to copy it can help us create more efficient ways to process data on computers,” says Mirasso.

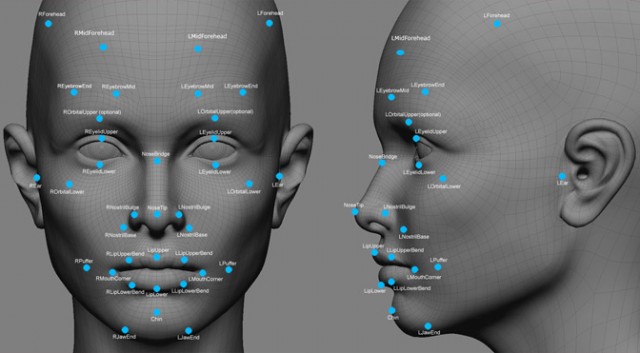

The brain can also contribute to improve facial and voice recognition engines. Although computers are more efficient than humans when calculating, for example, we are much better when it comes to differentiating faces and voices. Research about what makes our brains specialists in these tasks is a way to improve computer systems that try to distinguish different faces and sounds.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Complex networks and neuroscience

Redes complexas e neurociência

Ao longo da Escola em Redes Complexas e Neurociências, realizada no ICTP-SAIFR entre os dias 28 de setembro e 16 de outubro, Claudio Mirasso, da Universitat de les Illes Balears, da Espanha, falou sobre a relação entre redes complexas e estudos do cérebro. O pesquisador, um dos organizadores do evento, ressaltou como, por um lado, ideias da Física podem ajudar em trabalhos de neurociência e, por outro, como a maneira do cérebro funcionar pode contribuir para pesquisas de ciências exatas.

Funcionamento Cerebral

Um dos interesses de Mirasso é entender a sincronia entre diferentes regiões do cérebro.

“Com estudos de eletroencefalografia (EEG) vemos que regiões do cérebro, muitas vezes não conectadas estruturalmente, estão sincronizadas”, diz ele. “Através de estudos com redes complexas, buscamos compreender como ocorre essa sincronia e a troca de informações entre as diferentes áreas cerebrais”.

Um dos motivos pelos quais isso ocorre, segundo o pesquisador, é que as regiões têm funções semelhantes ou complementares. Quando vemos um objeto, por exemplo, informações sobre sua forma, cor e posição no espaço chegam ao cérebro, e diferentes áreas são ativadas para processar esse conjunto de informações.

“Entre nossos resultados mais recentes, observamos que o tálamo é um dos principais responsáveis pela coordenação dessa sincronia”, afirma Mirasso.

Processamento de informação

Se redes complexas ajudam a entender como o cérebro funciona, o contrário também pode acontecer – principalmente quando se trata de processamento de informações.

“Estamos vivendo a era da informação”, diz Mirasso. “A quantidade de dados aumenta a cada dia e, por isso, precisamos de novas formas para processar toda essa informação”.

Uma das maneiras de tornar o processamento mais eficiente é separar, previamente, apenas os dados de interesse. Essa técnica é a mesma empregada pelo cérebro: todos os segundos somos bombardeados com milhares de estímulos visuais, sensoriais, auditivos e de outras naturezas. Entretanto, apenas o que é relevante é processado.

“Estudar como o cérebro filtra e processa informação e tentar copiá-lo pode nos ajudar a criar maneiras mais eficientes de processar dados em computadores”, afirma Mirasso.

O cérebro também pode contribuir no aprimoramento de mecanismos de reconhecimento facial e de voz. Apesar de computadores serem mais eficientes do que humanos ao realizar cálculos, por exemplo, nós somos muito superiores para diferenciar rostos e vozes. Pesquisar o que torna nossos cérebros especialistas nessas funções é um caminho para aprimorar sistemas computacionais que tentam discernir diferentes faces e sons.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Redes complexas e neurociência

Colloquium discusses complex networks and evolution

In last Wednesday’s colloquium, researcher Roberto Andrade, from the Universidade Federal da Bahia, talked about his latest works involving complex networks for the study of evolution. Andrade and his group propose a new method for organizing species and their evolution, traditionally done through phylogenetic trees based on morphology and molecular characteristics.

“Our proposal is to classify organisms based on similarities of components involved in the synthesis of basic molecules”, says Andrade. “In our work, we studied fungi based on chitin. Then, in a more ambitious project, we studied the evolutionary origins of the mitochondria”.

The researcher explains that many organisms have their own set of enzymes to obtain a molecule that is found in many different species. Therefore, by studying differences between cell machinery, it’s possible to classify organisms by their genetic proximity.

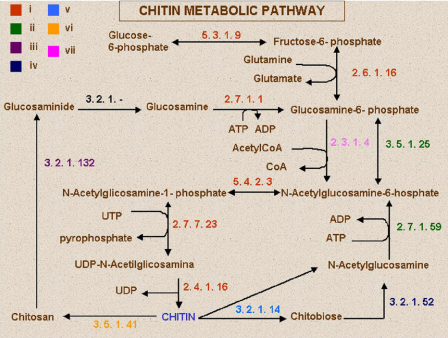

This situation happens, for instance, with chitin – a molecule that is the main component of fungal cell wall. Different species, however, obtain chitin through different processes. Andrade and his group used the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database to compare the molecular mechanisms of various species.

“The classification we reached coincided 100% with other phylogenetic trees”, says Andrade. “However, the method we used to obtain the final classification is faster”.

Origins of the mitochondria

“After this work, we got more ambitious”, says Andrade. “We started working on a project to discover the evolutionary origins of the mitochondria”.

Although many theories attempt to explain the evolution of the mitochondria, the issue still intrigues scientists. For those unfamiliar with biology, mitochondria is an organelle that has its own DNA. Some hypothesis, such as Endosymbiotic Theory, proposes that mitochondria originated when a prokaryotic organism (which has no cell nucleus) started living in symbiosis with a eukaryotic cell (which has cell nucleus).

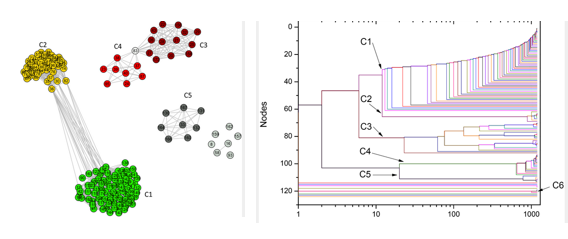

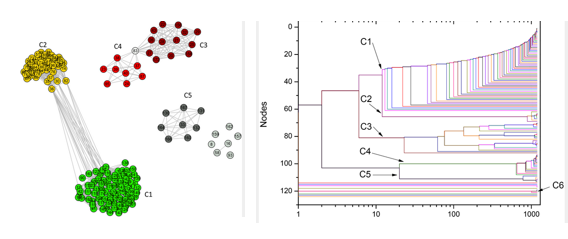

In the left, complex networks shows the proximity of different groups; in the right, the resulting phylogenetic tree

This time, the study was based on the ATP synthesis process – this molecule is considered a cellular fuel, since cells obtain energy by breaking it. Andrade and his group compared the molecular structures that lead to ATP synthesis in bacteria and in mitochondria, to find out which bacteria were most genetically close to the organelle.

“Our main result was that Rickettsiales bacteria are not closely related to mitochondria”, says Andrade. “The work indicated that Rhodobacterales, Rhizobiales and Rhodospirillales are groups closer to the organelle”.

The work was published this year in PLOS and can be found here.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Colloquium discusses complex networks and evolution

Colóquio discute redes complexas e evolução

No colóquio da última quarta-feira, o pesquisador Roberto Andrade, da Universidade Federal da Bahia, falou sobre seus trabalhos mais recentes envolvendo redes complexas para o estudo da evolução. Andrade e seu grupo propõem um novo método para a organização de seres vivos e de sua evolução, tradicionalmente feita através de árvores filogenéticas baseadas em morfologia e características moleculares.

“Nossa proposta é classificar organismos com base em similaridades de componentes envolvidos na síntese de moléculas básicas”, diz Andrade. “Em um trabalho, estudamos fungos baseados em quitina. Depois, em um projeto mais ambicioso, tentamos estudar a origem evolucionária das mitocôndrias”.

O pesquisador explica que muitos organismos possuem seu próprio “conjunto” de enzimas para obter uma molécula que é encontrada em várias espécies diferentes. Por conta disso, é possível classificar a proximidade genética entre elas ao estudar as diferenças entre suas maquinarias celulares.

Exemplo dessa situação ocorre com a quitina – a molécula é o principal componente da parede celular de fungos. Diferentes espécies, porém, obtêm a quitina através de processos distintos. Andrade e seu grupo utilizou como base os dados do NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) e comparou os mecanismos moleculares de diversas espécies.

“A classificação à qual chegamos coincidiu completamente com as de árvores filogenéticas anteriores”, diz Andrade. “A diferença é que o método que usamos é mais rápido para se obter a classificação final”.

Origens da mitocôndria

“Depois desse trabalho, ficamos mais ambiciosos”, conta Andrade. “Começamos um trabalho para tentar descobrir a origem evolutiva da mitocôndria”.

Apesar de muitas teorias tentarem explicar a evolução da mitocôndria, a questão ainda intriga cientistas. Para quem não está familiarizado com biologia, a mitocôndria é uma organela que possui seu próprio DNA. Algumas hipóteses, como a Teoria Endossimbiótica, propõem que a mitocôndria teve sua origem a partir de um organismo procarionte (que não tem núcleo celular) que viveu em simbiose com uma célula eucarionte (que tem núcleo celular).

À esquerda, redes complexas mostram a proximidade entre diferentes grupos; à direita, a árvore filogenética resultante

O estudo, dessa vez, foi baseado no processo de síntese de ATP – molécula que é uma espécie de combustível celular, pois sua quebra fornece energia para as células. Andrade e seu grupo comparou as estruturas moleculares que levam à síntese de ATP em bactérias e em mitocôndrias, para tentar descobrir qual bactéria estava mais geneticamente próxima da organela.

“Nosso principal resultado foi que bactérias da ordem Rickettsiales não tem relação próxima com mitocôndrias”, diz Andrade. “O trabalho indicou que Rhodobacterales, Rhizobiales e Rhodospirillales são grupos mais próximos da organela”.

O trabalho foi publicado esse ano na revista científica PLOS e pode ser visto aqui.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Colóquio discute redes complexas e evolução

Studying evolution and cooperation with Game Theory and Complex Networks

In the second week of the School on Complex Networks and Neuroscience, the lectures of Jesús Gómez-Gardeñes discussed how Game Theory ideas can help in studies of biology and evolution. His research focus especially on the mechanisms related to cooperation and imitation behavior in human populations.

Game Theory

Game Theory ideas have applications in several areas, from economics to biology. The main purpose of the area is to find the best strategy, or alternative, when we face a problem in nature or society.

“With Game Theory we can “mathematize” conflicts and dilemmas, which allows us to calculate the best solution for them”, says Gardeñes.

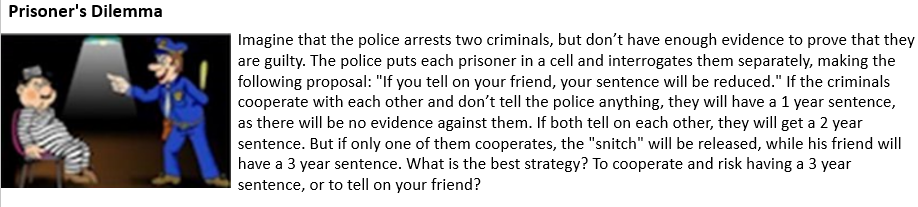

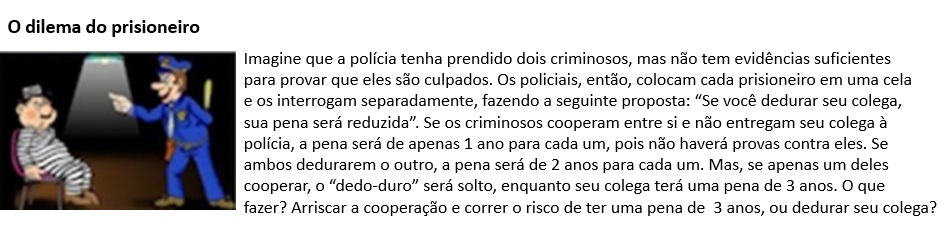

A classic example of the area is the “Prisoner’s Dilemma”.

One way to solve problems like this one is to calculate the Nash Equilibrium for the situation – the result will show what strategy is the best one. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma case, telling on your friend is the best option.

Evolution

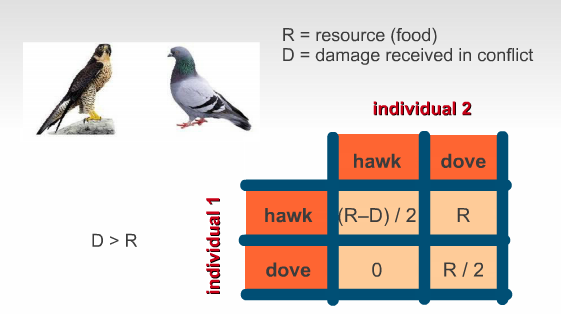

Game Theory can be applied in studies of biology and evolution. One of the first works in the area, “The logic of animal conflict,” was written by John Maynard Smith and George Price in 1973 and published in Nature. In the article, the researchers imagine a situation where two species, like hawks and doves, compete for the same resource.

In this simplified case, imagine that when a dove competes with another dove for food, they share the resource. When a hawk competes with a dove, the hawk gets the resource. And when two hawks compete for food, they will fight – their final result will be the resource minus the damage they take in the conflict. So, what species would be favored by evolution?

“Game Theory can show how different strategies adopted by different species have different success rates”, explains Gardeñes. “So the process of natural selection will favor animals that adopt the strategy that provides the best results”.

In the example between hawks and doves, if the damage caused by the conflict between hawks is large, the dynamic tends toward an equilibrium, suggesting that the two species can coexist. When there are many hawks, the chances of two animals of this species meeting and fighting is high, favoring doves. When there are many doves, hawks are favored as they will have a good chance of winning the resource. In Game Theory, hawks and doves can represent different types of animals or different types of behavior of individuals of the same species.

Cooperation

According to Game Theory ideas, in most situations cooperation is not a strategy that would succeed in nature. Therefore, several studies try to understand how cooperation emerged, evolved and managed to survive in a great variety of communities. Some hypotheses say that this strategy favors the preservation of genes, as there is the possibility of increasing the chances of survival of your family members if you cooperate with them. In other communities, individuals that don’t cooperate might be punished.

“In my research, I try to understand cooperation in human populations”, says Gardeñes. “Through studies of complex networks, we can better understand how people relate to each other”.

Gardeñes points out that humans are different from animals, as they can change strategy at any time. While a dove can’t choose to behave like a hawk, we can change our behavior. One of the reasons that make us change our strategy is by observation: when we see someone else adopt a different strategy from our own and be successful, we can choose to imitate him.

“My work also aims to understand the mechanisms of imitation strategies in humans,” says Gardeñes. “Our objective is to create simulations that are as close to reality as possible. One of the ways of doing this is to add multiple networks to the system: related to work, friendships, family and so on”.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Studying evolution and cooperation with Game Theory and Complex Networks

Estudando evolução e cooperação com Teoria de Jogos e Redes Complexas

Na segunda semana da Escola em Redes Complexas e Neurociência, as palestras de Jesús-Gómez Gardeñes mostraram como ideias de Teoria de Jogos podem ajudar em estudos de biologia e evolução. Suas pesquisas tentam compreender, principalmente, os mecanismos relacionados à cooperação e comportamentos de imitação em populações humanas.

Teoria de Jogos

As ideias de Teoria de Jogos têm aplicações em diversas áreas, de economia à biologia. O principal objetivo ao se usar essas ideias é descobrir qual a melhor estratégia, ou alternativa, quando nos deparamos com um problema na natureza ou na sociedade.

“Com a Teoria de Jogos podemos “matematizar” conflitos e dilemas, o que nos permite calcular a melhor solução para eles”, diz Gardeñes.

Um exemplo clássico da área é o “Dilema do Prisioneiro”.

Uma das formas de resolver problemas como esse é calcular o Equilíbrio de Nash para a situação – ele mostrará qual a melhor estratégia a ser adotada. No caso do Dilema do Prisioneiro, dedurar o colega é a melhor opção.

Evolução

A Teoria de Jogos pode ser aplicada aos estudos de biologia e evolução. Um dos primeiros trabalhos na área, “A lógica de conflitos animais”, foi escrito por John Maynard Smith e George Price, em 1973, e publicado na revista Nature. No artigo, os pesquisadores imaginam uma situação onde duas espécies, como gaviões e pombos, competem por um mesmo recurso.

Nesse caso simplificado, imagina-se que quando um pombo disputa comida com outro pombo, os animais dividem o recurso entre si. Quando um gavião encontra um pombo, o gavião fica com o recurso. E quando dois gaviões se encontram, eles competem pela comida: o ganho deles será o recurso menos o dano causado pela briga entre ambos. Nesse caso, qual espécie seria favorecida pela evolução?

“A Teoria de Jogos pode mostrar como diferentes estratégias, adotadas por diferentes espécies, têm taxas de sucesso diferentes”, explica Gardeñes. “Assim, o processo de seleção natural irá favorecer os animais que adotam a estratégia que apresenta os melhores resultados”.

No exemplo entre gaviões e pombos, se o dano causado pela briga entre gaviões é grande, a dinâmica tende para um equilíbrio, mostrando que as duas espécies podem coexistir. Quando há muitos gaviões, as chances de dois animais dessa espécie se encontrarem e brigar é alta, favorecendo pombos. Quando há muitos pombos, os gaviões são os favorecidos, pois terão grandes chances de ganhar o recurso. Na Teoria de Jogos, gaviões e pombos podem representar animais diferentes ou tipos de comportamentos de indivíduos de uma mesma espécie.

Cooperação

De acordo com ideias de Teoria de Jogos, na maioria das situações a cooperação não é uma estratégia que teria sucesso na natureza. Por isso, diversas pesquisas tentam entender como a cooperação surgiu, evoluiu e conseguiu se manter em uma grande variedade de comunidades de seres vivos. Algumas hipóteses dizem que essa estratégia favorece a preservação dos genes, pois há a possibilidade de aumentar as chances de sobrevivência de membros da sua família ao cooperar com eles. Em outras comunidades, quem não coopera pode ser punido.

“Em minhas pesquisas, tento entender como a cooperação ocorre em populações humanas”, diz Gardeñes. “Por meio de estudos com redes complexas, podemos compreender melhor como pessoas se relacionam”.

Gardeñes ressalta que estudar humanos é diferente de estudar animais pelo fato de que nós podemos mudar de estratégia a qualquer momento. Enquanto um pombo não pode escolher se comportar como um gavião, nós podemos mudar nosso comportamento. Um dos motivos que nos fazem mudar de estratégia é pela observação de outros indivíduos: quando vemos outra pessoa adotar uma estratégia diferente da nossa e ser bem-sucedido, podemos escolher imitá-lo.

“Meu trabalho também busca entender como funcionam os mecanismos e as estratégias de imitação em seres humanos”, diz Gardeñes. ”O objetivo com esses estudos é criar simulações que se aproximem o máximo possível da realidade. Um dos jeitos de se fazer isso é adicionar múltiplas redes: relacionadas a trabalho, amizades, família e etc”.

Continue Reading | Comments Off on Estudando evolução e cooperação com Teoria de Jogos e Redes Complexas